Questions and Answers about Scoliosis in Children and Adolescents

This publication defines scoliosis and provides information about how it is diagnosed and treated in children and adolescents. You may be interested in contacting one or more of the organizations listed at the end of the publication for more information. If you have further questions, you may wish to discuss them with your health care provider.

What Is Scoliosis?

Scoliosis is a musculoskeletal disorder in which there is a sideways curvature of the spine, or backbone. The bones that make up the spine are called vertebrae. Some people who have scoliosis require treatment. Other people, who have milder curves, may need to visit their doctor for periodic observation only.

- Who Gets Scoliosis?

- What Causes Scoliosis?

- How Is Scoliosis Diagnosed?

- Does Scoliosis Have to Be Treated? What Are the Treatments?

- Are There Other Ways to Treat Scoliosis?

- What About Bracing?

- If the Doctor Recommends Surgery, Which Procedure Is Best?

- Can People With Scoliosis Exercise?

- What Research Is Being Conducted on Scoliosis?

- Where Can People Get More Information About Scoliosis?

Illustrations

Who Gets Scoliosis?

People of all ages can have scoliosis, but this publication focuses on children and adolescents. Adolescent idiopathic scoliosis (scoliosis of unknown cause) is the most common type and typically occurs after the age of 10. Girls are more likely than boys to have this type of scoliosis. Because scoliosis can run in families, a child who has a parent, brother, or sister with idiopathic scoliosis should be checked regularly for scoliosis by the family doctor.

What Causes Scoliosis?

In most cases, the cause of scoliosis is unknown; this is called idiopathic scoliosis. Before concluding that a person has idiopathic scoliosis, the doctor looks for other possible causes, such as injury or infection. Causes of curves are classified as either nonstructural or structural.

- Nonstructural (functional) scoliosis. A structurally normal spine that appears curved. This is a temporary, changing curve. It is caused by an underlying condition such as a difference in leg length, muscle spasms, or inflammatory conditions such as appendicitis. Doctors treat this type of scoliosis by correcting the underlying problem.

- Structural scoliosis. A fixed curve that doctors treat case by case. Sometimes structural scoliosis is one part of a syndrome or disease, such as Marfan syndrome, an inherited connective tissue disorder. In other cases, it occurs by itself. Structural scoliosis can be caused by neuromuscular diseases (such as cerebral palsy, poliomyelitis, or muscular dystrophy), birth defects (such as hemivertebra, in which one side of a vertebra fails to form normally before birth), injury, certain infections, tumors (such as those caused by neurofibromatosis, a birth defect sometimes associated with benign tumors on the spinal column), metabolic diseases, connective tissue disorders, rheumatic diseases, or unknown factors (idiopathic scoliosis).

How Is Scoliosis Diagnosed?

Doctors take the following steps to evaluate patients for scoliosis:

- Medical history. The doctor talks to the patient and the patient’s parent(s) and reviews the patient’s records to look for medical problems that might be causing the spine to curve, for example, birth defects, trauma, or other disorders that can be associated with scoliosis.

- Physical examination. The doctor looks at the patient’s back, chest, pelvis, legs, feet, and skin. The doctor checks if the patient’s shoulders are level, whether the head is centered, and whether opposite sides of the body look level. The doctor also examines the back muscles while the patient is bending forward to see if one side of the rib cage is higher than the other.

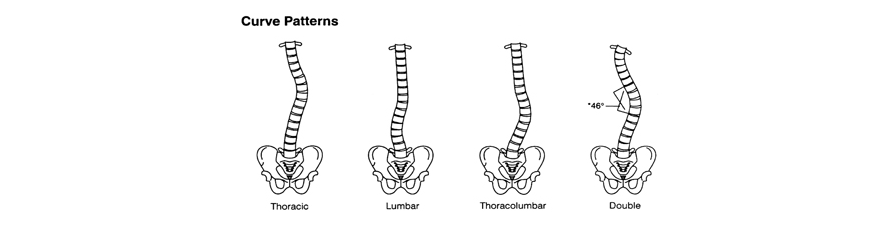

- X-ray evaluation. An x ray of the spine can confirm the diagnosis of scoliosis. The doctor measures the curve on the x-ray image. He or she finds the vertebrae at the beginning and end of the curve and measures the angle of the curve (see “Curve Patterns” diagram).

Doctors group curves of the spine by their location, shape, pattern, and cause. They use this information to decide how best to treat the scoliosis.

- Location. To identify a curve’s location, doctors find the apex of the curve (the vertebra within the curve that is the most off-center); the location of the apex is the “location” of the curve. A thoracic curve has its apex in the thoracic area (the part of the spine to which the ribs attach). A lumbar curve has its apex in the lower back. A thoracolumbar curve has its apex where the thoracic and lumbar vertebrae join (see “Normal Spine” diagram).

- Shape. The curve usually is s- or c-shaped.

- Pattern. Curves frequently follow patterns that have been studied in previous patients (see “Curve Patterns” diagram). The larger the curve is, the more likely it will progress (depending on the amount of growth remaining).

Does Scoliosis Have to Be Treated? What Are the Treatments?

Many children who are sent to the doctor by a school scoliosis screening program have very mild spinal curves that do not need treatment. When treatment is needed, the doctor may send the child to an orthopaedic spine specialist.

The doctor will suggest the best treatment for each patient based on the patient’s age, how much more he or she is likely to grow, the degree and pattern of the curve, and the type of scoliosis. The doctor may recommend observation, bracing, or surgery.

- Observation. Doctors typically follow patients without treatment and re-examine them every few months when the patient is still growing (is skeletally immature) and the curve is mild.

- Bracing. Doctors may advise patients to wear a brace to stop a curve from getting any worse in patients who are still growing with moderate spinal curvature. As a child nears the end of growth, the indications for bracing will depend on how the curve affects the child’s appearance, whether the curve is getting worse, and the size of the curve.

- Surgery. Doctors may advise patients to have surgery to correct a curve or stop it from worsening when the patient is still growing, has a curve that is severe, and has a curve that is getting worse.

Are There Other Ways to Treat Scoliosis?

Some people have tried other ways to treat scoliosis, including manipulation by a chiropractor, electrical stimulation, dietary supplements, and exercise. However, studies of these treatments have not been shown to prevent curve progression, or worsening. Patients may wish to exercise for the effects on their general health and well-being.

What About Bracing?

The decision about which brace to wear depends on the type of curve and whether the patient will follow the doctor’s directions about how many hours a day to wear the brace.

Braces must be selected for the specific curve problem and fitted to each patient. To have their intended effect (to keep a curve from getting worse), braces must be worn every day for the full number of hours prescribed by the doctor until the child stops growing.

If the Doctor Recommends Surgery, Which Procedure Is Best?

Many surgical techniques can be used to correct the curves of scoliosis. The main surgical procedure is correction, stabilization, and fusion of the curve. Fusion is the joining of two or more vertebrae. There are different ways to straighten the spine and different implants to keep the spine stable after surgery. (Implants are devices that remain in the patient after surgery to keep the spine aligned.) The decision about the type of implant will depend on the cost, the size of the implant, which depends on the size of the patient; the shape of the implant; its safety; and the experience of the surgeon. Each patient should discuss his or her options with at least two experienced surgeons.

Patients and parents who are thinking about surgery may want to ask the following questions:

- What are the benefits from surgery for scoliosis?

- What are the risks from surgery for scoliosis?

- What techniques will be used for the surgery?

- What devices will be used to keep the spine stable after surgery?

- Where will the incisions be made?

- How straight will the spine be after surgery?

- How long will the hospital stay be?

- How long will it take to recover from surgery?

- Is there chronic back pain after surgery for scoliosis?

- Will the patient’s growth be limited?

- How flexible will the spine remain?

- Can the curve worsen or progress after surgery?

- Will additional surgery be likely?

- Will the patient be able to do all the things he or she wants to do following surgery?

Can People With Scoliosis Exercise?

Although exercise programs have not been shown to affect the natural history of scoliosis, exercise is encouraged in patients with scoliosis to minimize any potential decrease in functional ability over time. It is very important for all people, including those with scoliosis, to exercise and remain physically fit. Girls have a higher risk than boys of developing osteoporosis (a disorder that results in weak bones that can break easily) later in life. The risk of osteoporosis can be reduced in women who exercise regularly all their lives. Also, weight-bearing exercise, such as walking, running, soccer, and gymnastics, can increase bone density and help to prevent osteoporosis. For both boys and girls, exercising and participating in sports can also improve their general sense of well-being.

What Research Is Being Conducted on Scoliosis?

Researchers supported by the National Institutes of Health (NIH) are exploring genetic and neurological factors that may cause idiopathic scoliosis in an effort to identify targets for prevention and new treatments.

In one study, a randomized clinical trial, scientists are developing strategies to improve clinical decision making with respect to the nonoperative management (bracing versus watchful waiting) of idiopathic scoliosis in adolescents.

Researchers continue to examine how a variety of braces, surgical procedures, and surgical instruments can be used to straighten the spine or to prevent further curvature. They are also studying the long-term effects of both scoliosis fusion and the long-term effects of untreated scoliosis.

More information on research is available from the following websites:

- National Institutes of Health (NIH) Clinical Research Trials and You was designed to help people learn more about clinical trials, why they matter, and how to participate. Visitors to the website will find information about the basics of participating in a clinical trial, first-hand stories from actual clinical trial volunteers, explanations from researchers, and links to how to search for a trial or enroll in a research-matching program.

- ClinicalTrials.gov offers up-to-date information for locating federally and privately supported clinical trials for a wide range of diseases and conditions.

- NIH RePORTER is an electronic tool that allows users to search a repository of both intramural and extramural NIH-funded research projects from the past 25 years and access publications (since 1985) and patents resulting from NIH funding.

- PubMed is a free service of the U.S. National Library of Medicine that lets you search millions of journal citations and abstracts in the fields of medicine, nursing, dentistry, veterinary medicine, the health care system, and preclinical sciences.

Where Can People Get More Information About Scoliosis?

National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases (NIAMS)

Information Clearinghouse

National Institutes of Health

Other Resources

National Scoliosis Foundation

Website: http://www.scoliosis.org

The Scoliosis Association, Inc.

Website: http://www.scoliosis-assoc.org

Scoliosis Research Society

Website: http://www.srs.org

American Physical Therapy Association

Website: http://www.apta.org

Acknowledgments

The NIAMS gratefully acknowledges the assistance of the following individuals in the preparation and review of the original version of this publication: Stuart Weinstein, M.D., University of Iowa, Iowa City, IA; and John Lonstein, M.D., University of Minnesota, Minneapolis, MN; and James Panagis, M.D., NIAMS/NIH.

Credits & Documentation references